For the past decade or so, summer has begun for me with a visit to Borris in Co. Carlow. The wonderful Festival of Writing and Ideas fills my mind with new thoughts and interesting opinions and books-I-need-to-read lists that crowd out and chase away the CBAs and the lesson plans and the reports. This year I heard Fintan O’Toole being interviewed by fellow journalist Gary Younge on the state in which we find ourselves. O’Toole spoke as eloquently as ever, touching on the heft of the multi-nationals in influencing Irish public policy, a heft that is sometimes felt in terms of direct demands (or requests if you want to be polite), but more insidiously by a mindset of solicitation that prioritises shot-term attractiveness over long-term, values-driven development.

I am not sure to what extent the multi-nationals bother themselves with intervening in our education system, at least at the primary and secondary levels. That they call for more investment is fine. That we need them to say it is shameful. What I am certain of is that they don’t need to intervene at the level of curriculum and assessment, because the Department of Education actively seeks to pre-emptively please our current and potential inward investors.

When thinking about schooling in Ireland and how it might play a role in making us look like we have our act together, the problem might have seemed that the system looked a bit old-fashioned, and was too egalitarian. In 2016 the then-Minister for Education Richard Bruton announced his “ambition…to make Ireland the best education and training service in Europe” Few at the time or since questioned the use of the word “service”. I imagine that most people didn’t even notice as they do indeed think of education as a personal service to their own family. Increasingly, and of course I generalise, the kind of parents who see education as a service are used to having most services of which they avail pre-emptively structured around their anticipated requirements. Their requirements are simple. They want their child’s self-esteem and wellbeing nurtured. They want them to do lots of maths. They want a system that ensures that their middle-class child of middling ability isn’t bothered too much by the threat of being overtaken by a bright working-class child who works hard, is taught well, and excels in an anonymised assessment regime.

Although no doubt many parents and other voters took Richard Bruton’s “service” to mean a direct-to-consumer product in which they were the consumer, it is also plausible that the word was used in a separate sense. Perhaps the end-user of the education service is not the child or the child’s family. Maybe the child is the product and the consumers are the child’s potential employers. This sounds heartless but it is one arc of an economic circle whereby children are formed into an available workforce which attracts inward investment and this inward investment will raise our economic wellbeing, part of which bounty will be invested in educating the next generation and so on. This argument might have held some water decades ago and we were told it often enough when we were in school, but it has become a psychological fig-leaf that covers the infinitely more potent attraction of tax incentives.

The narrative of our broken education system has been essential in order to justify remaking the system, but the Department cannot admit that its purpose is to make Ireland more attractive as a location for business. They must talk instead about raising standards, implying that inward investment is but a happy byproduct of excellence. Yet these standards are rarely spoken of in terms of standards of attainment, Instead they are standards of delivery: an education system that exists to “meet the existing and future needs of children”. Children are “supported” rather than “taught” (you might say that teaching someone is supporting them to learn, but in that case why not just use the verb “teach”?), while Wellbeing is “at the forefront of teachers’ work”.

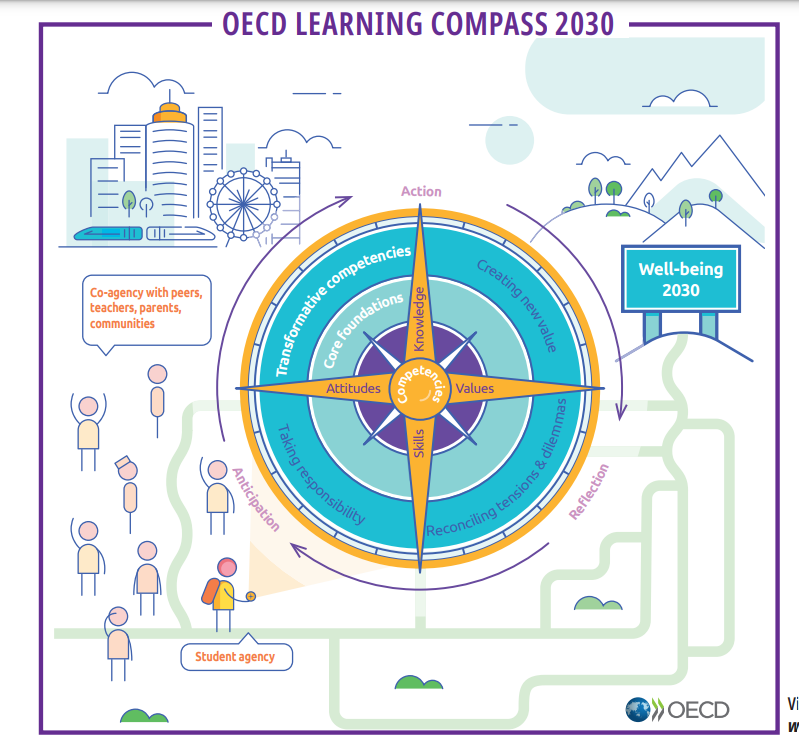

The emerging new curriculum takes its lead almost entirely from the OECD’s vision for the future of education (what used to be called “21st century learning”). The forthcoming reforms of Senior Cycle are already being rumoured to be based on the OECD Learning Compass 2030, which is itself based on emerging “megatrends” and is full of vague aspirations such as developing young people’s “transformative competencies” and “co-agency with peers, teachers, parents, communities”. Reform of assessment will be an even more radical version of what has been done at Junior Cycle: replacing externally-assessed, syllabus based examinations with continuous assessment and accreditation for non-academic “other areas of learning”. Both continuous assessment and awarding credit for extra-curricular activities will both, of course, function very well as middle-class ramps that will ensure the children of the well-paid can continue to progress to third-level education in a transition that is so inevitable it can appear natural.

There isn’t much space in this vision for the arts, especially not for literature. The arts in general have been incorporated into the acronym STEAM, where they play the role of handmaiden to engineering and technology, shunted away from ideas of culture and the humanities. The downgrading of literature is my own particular worry, but art and music have also been hit, not least because they have been starved of funding that is going instead towards software licensing and trolleyfuls of iPads. Anecdotally, secondary schools have cut back on the time for art and for music in order to comply with the ring-fenced 400 hours of curricular time for “wellbeing”. Most are no longer in a position to offer a full year of “taster” subjects in first year; a practice whereby in-coming students had at least one full school year where they received instruction in both art and music from teachers with specialist degrees and expertise.

The teaching of literature within subject of English – the first to undergo reform at Junior Cycle – has been the greatest curricular casualty of recent changes A quick word-search of the NCCA’s 2012 Background Paper and Brief for the Review of English shows 25 results for “reading”, 18 for “literature”, 7 for “knowledge” and 66 for “digital”. This was a taste of what was to come. A 2023 NCCA-commissioned report on the role and selection of prescribed texts, while opening with the declaration that “Literature plays many roles across the spectrum of education”, goes on to clarify:

“However, the word “literature” is value-laden. For many it creates an expectation of literary works of art, imbued with longevity and cultural importance and therefore with high cultural capital. For this reason, the specification and syllabus for English at junior cycle and Leaving Certificate use the broader term “texts” to include literary and non-literary texts that students will encounter, explore and model in their experience in the English classroom. This may include novels, novellas, poetry, prose, drama, written verse, spoken word, graphic novels, travelogues, blogs, film, biopics, biographies, essay, articles, podcasts and more.”

The authors of this report mean well and – having presumably at some point come across Bourdieu’s concept of habitus – are trying to design a curriculum that is inclusive and socially progressive. They are working within the confines of a system where literature has no importance, and where education has no importance other than as a prop in our staged window of national attractiveness.

You won’t ever find anyone (unless you go to Florida) who says they are against the teaching of literature. Yet the place of literature is increasingly on the margins. English as a subject overall has lost its identity as a core subject and, even more strikingly, literature now occupies less and less space within this reduced space.

The point of literature is its pointlessness, by which I mean its irrelevance to the economic circle model of education. It is a counterweight without which we are taken ever more off-kilter until we find ourselves somewhere we are not quite sure is real but have no idea how any other existence might be possible. And even beyond this value as a counterweight – a value that is shared by all the arts – literature has further value than cannot be expressed in terms extraneous to the thing itself. Literature is not a luxury, but a necessity as Dr Philip McGowan, Professor of American Literature at Queens University, explains here so well in his inaugural lecture “Literature and the Right to Write”. His words are addressed to Rishi Sunak yet the problem he describes – the displacement of literature within the school curriculum – is arguably even worse here than it is in the constituent parts of the UK education system.

“Without literature, without art, we are diminished….It’s the subjects that comprise the arts and humanities that truly make the reckoning of who we are, who we have been and who we can become. Without art to articulate the darkness as well as be the light of being, we have nothing beyond merely existing in an abyss of thoughtless meaninglessness…..Culture, art, literature are not just a right, they are a necessity.”

Over the first three years of secondary education, English has a minimum time allocation of 240 hours (remember, the minimum for wellbeing is 400), nominally the same as for Maths but in practice almost all schools give more time to Maths. Between the blogs and the travelogues and the tweets and the podcasts, there is not much time left for children to encounter actual literature in the classroom. Even when they do, it is at a breakneck pace. Gill and Macmillan recently boasted that their edition of “Romeo and Juliet” is designed to cover the play in its entirety, along with themes, characterisation and questions of stage-craft, in between four and six weeks. To take the lower end of that time frame, at four forty minute classes a week that’s less than 11 hours of Shakespeare in three years.

As for the final assessment, the last time the Shakespearean play was a compulsory element on the examination was 2019. In 2023, candidates could choose to answer on a play by Shakespeare or one of the two novels they had studied. The list of prescribed novels may include “The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde”, “Sense and Sensibility” and “Things Fall Apart” but teachers are arguably disincentivised from choosing such rich and challenging texts for two reasons. The first is that it is hard to cover them in any meaningful depth in the meagre time allowed, and a second, related reason is that choosing simpler material allows for more time to “teach to the test” i.e. practice with past and sample exam papers to hone shallow form-filling skills and practice concocting coherent responses to stimulus material such as the example below from 2019.

2019 Higher Level English Junior Cycle https://www.examinations.ie/archive/exampapers/2019/JC002ALP000EV.pdf

Professor McGowan describes recent curricular change in Northern Ireland as a “covert attack on literature” whereby “short-term decision-making is stripping our society of that which defines us”. The same point can be made even more strongly on this side of the border. In fashioning our curriculum and its assessment around what we hope will attract economic investment, we are like a beautiful but insecure young person who, inspired by Instagram, opts for lip injections to achieve a pout that is “in line with international best practice”. It’s not about enhancing what we already have and appreciating how it functions; instead we are aiming for maximum superficiality, a synthetic simulacrum of excellence where – as in Garrison Keillor’s “Lake Woebegone” – all children will be above average, and will have studied programming rather than poetry. Reading anything will be the preserve of what some populist aspiring leader will reasonably point to as the out-of-touch élite. Centuries of literary heritage will be preserved only in academia and, what is much worse, we may never hear the voices of the Naoise Dolans and Seán Hewitts and Victoria Kenneficks of the future.