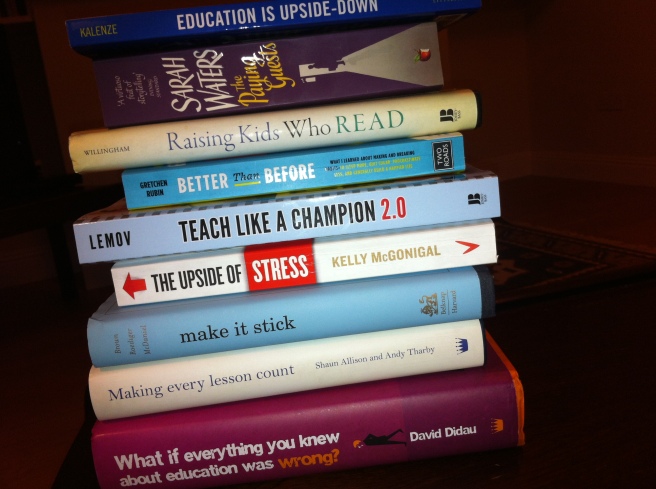

Here are some of the books – educational and otherwise – that have made an impact on me in 2015. These are in no particular order, and you may spot that some were published last year or even earlier. My criterion is that I read them for the first time this year, and I admit freely to being chronically behind the curve.

Here are some of the books – educational and otherwise – that have made an impact on me in 2015. These are in no particular order, and you may spot that some were published last year or even earlier. My criterion is that I read them for the first time this year, and I admit freely to being chronically behind the curve.

“The Paying Guests” by Sarah Waters and “Maddaddam” by Margaret Atwood.

My contemporary fiction reads of the year. Very different genres, equally engrossing. I sped through the former in less than twenty-four hours. Waters is unparalleled in her ability to recreate distinctive eras from Britain’s past – so much so her novels read almost like contemporary texts of the period – and this time she turns her attention to the London suburbs of 1922. The Great War has been over for four years and Frances and her widowed mother are still coming to terms with a dramatically changed social and economic order. They do the previously unthinkable and take in lodgers: the “paying guests” of the title. The genteel term is typical of the language of sheltered women who speak mostly in euphemisms; their home, and Frances’ world, is invaded by a young couple who bring passion and drama along with a gramophone and some cheap “pseudo-Persian rugs”. The plot is satisfyingly clever and Waters’ pacing is impeccable. It is rare indeed to find such a breakneck page-turner so beautifully written.

Atwood’s “Maddadam” is the third instalment in the dystopian trilogy she began with “Oryx and Crake”. I haven’t read the middle book “The Year of the Flood” (on the list for 2016) but caught up fairly lively. Having said that, I do feel that had I not read “Oryx and Crake”, albeit some years ago now, then a struggle with the underlying premise would have undermined my reading pleasure. And what pleasure! Atwood is an adept at this genre; her grotesque inventions always have enough recognisable elements to let them ring disturbingly true. In “Oryx and Crake” she showed us a new world in the not too distant future. It’s a controlled world of surveillance and medical miracles, most notably the engineering and breeding of Pigoons to supply organs for transplant into humans. This corrupt and unnatural order splinters and by “Maddadam” we are roaming a lawless, despoiled landscape only vaguely identifiable as America. Amid the science fiction and the cartoon violence, Atwood fills the book with introspective and very human characters, such as Toby a woman rendered infertile following botched egg-donation, and Zeb, who wonders if the plan devised by his mastermind brother, Adam, will save or doom what remains of humanity. We feel their confusion, their jealousies, their fears and ultimately their hope that some kind of future will emerge from the chaos.

Honourable fiction mentions include Colin Barrett’s “Young Skins”, Belinda McKeon’s “Tender”, Hilary Mantel’s “The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher” and Richard Ford’s “Independence Day” (I told you I was behind the curve).

Eric Kalenze “Education is Upside-Down”

I missed Kalenze’s talk at ResearchEd and was quite cross with myself afterwards as it was widely reported as one of the highlights. Reading this book, I can see why. It deals with the US education system and provides many interesting points of contrast and comparison. The book’s central metaphor is that education acts like an upside-down funnel; instead of bringing in those who set out(for whatever reason) on the margins and ensuring they’re ready to participate fully in society and its institutions, the funnel is positioned so these students slide off and only those who start out with every advantage fully profit from the system. Good for them (us, really. I was one such student), less good for society as a whole.

“Making Every Lesson Count” by Andy Tharby and Shaun Allison

How excited was I to learn that Tharby – author of this eminently practical and insightful blog – was bringing out a book? This collaboration with his colleague Allison broadens the English-specific advice in the blog and applies it to all subjects. Allison and Tharby are classroom teachers rather than researchers or academics and this shows in every line of this book. It’s based on six principles – challenge, explanation modelling, practice, feedback, questioning – each of which is clearly explained with realistic examples.

“Bringing Words to Life: Robust Vocabulary Instruction” by Isabel Beck, Margaret McKeown and Linda Kucan.

As recommended here by Andy Tharby, this is a very, very useful book on how to extract maximum vocabulary-extending value out of texts used in the classroom. My copy is in school, where I’ve used it this term in conjunction with Neil Gaiman’s “The Graveyard Book” with my first years. Thanks to techniques in BWtL, the kids are now confident using words like “treason”, “writhing” and “reprehensible”. They also know what “offal”is, though they’re as likely to eat it as they are to enjoy a plate of “carrion”.

“What if Everything You Knew About Education Was Wrong?” by David Didau.

Eye-catching fuschia antidote to the tuar tairbh we were all fed on during the HDip and which keeps on giving through Department of Education and Skills. Didau, aka the Learning Spy, provides a comprehensive survey of ideas in education from feedback to lesson observation to how best to motivate students and takes well-earned delight in such heresies as “why formative assessment might be wrong”. As well as dispelling myths there’s plenty of information here about what might actually work.

“The Upside of Stress” by Kelly McGonigal

Not a teaching book, but being able to see the upside of stress is bound to make any teacher’s life easier. Although life’s not supposed to be easy, which is one the book’s central ideas. In the future I intend to draw heavily on McGonigal’s work for my upcoming companion-piece to Didau’s book. Mine will be called “What if Everything You Knew About Well-being was Wrong?” “The Upside of Stress” is a reasoned and compassionate book that recognises that facile calls for “resilience lessons” and “mental fitness” are less useful than seeing that, for most of us, stress is inextricably linked to the areas of our life that have the greatest potential to bring us meaning, purpose and even joy.

“Raising Kids Who Read” by Daniel Willingham.

Another book by the author of one of the my favourite books about teaching “Why Don’t Students Like School?”. Lots of thought-provoking stuff here, but as the title suggests, aimed mostly at parents.

“Teach Like a Champion 2.0” by Doug Lemov

I’m probably the only teacher on Earth who preferred the original version of this book. That might be because “Teach Like a Champion” was the first ever book about teaching I ever bought (apart from mandated HDip books and useless behaviour-management manuals written by idealistic gurus) and it opened my eyes to the possibility that teacher-led instruction might work better than buzzy, carousel, engaging, groupe-worke, relevant child-minding. In fairness, this probably is objectively better than the original, containing all the information in that one and even more.

“Make it Stick” By Peter C. Brown, Henry Roediger III and Mark A. McDaniel.

Not a teaching manual like Lemov’s book but of a theoretical exploration of learning. How to make it stick is a question that’s asked scandalously infrequently in teaching; we’re much more likely to be asked to consider how to make it interesting? how to engage pupils? (okay, we’re never asked this, I meant “how to engage learners?”), how can reinvent the group-work wheel? or how many acronyms can I fit into this forty-minute presentation? Making knowledge stick is largely what teaching aims to do, however, and there’s lots here to take into the classroom. One study referred to in the book that I found particularly interesting is about history of art students learning about the “defining characteristics of each artist’s style”. They were tested on how well they could attribute paintings. Interleaved practice, where students studied a painting by one artist, and then a painting by a different artist, was shown in the study to be more successful than massed practice where students studied one artist in a block before moving on to the next. I think this has implications for how we teach Leaving Cert poetry, where traditionally we “do” a poet, then move on to some other part of the course, before returning to “do” another poet.

“Better than Before” by Gretchen Rubin.

I’ve had heated debates about Rubin and her books. At least one friend of mine finds her self-improvement books insufferable, focused as they on the minutae of first-world problems like whether one can justify taking a taxi to the gym. While I disagree with the author and say “no, you can’t”, I also disagree with my friend and say that Rubin’s books are well-written and not meant to be taken too seriously. She does not promise to change the reader’s life and cleverly avoids all discussion of cognitive psychology or neuroscience as she’s intelligent enough to not fall for the Dunning-Kruger effect. Her latest is a light read that’s strangely satisfying with its mix of pop-psychology, highbrow references, life-hacks and mundane details from Rubin’s own life.

“Great Expectations” by Charles Dickens.

I studied this for the Inter, and am rereading it to get an early start on my first resolution for 2016, which is to read more classic fiction. More Austen and less Xposé. More Dostoyevsky and less DailyMailOnline. More George Eliot and fewer articles about how to stick to your New Year’s resolutions.

Happy 2016 🙂